A Fencing Life

Nick Evangelista

A Fencing Life

By Nick Evangelista

I have been writing about fencing for around 40 years. It seems longer. It should be noted, regarding this feature of my fencing life, that many people take umbrage at what I say. There is an article lurking somewhere on sport fencing’s cheerleader, fencing.net, entitled, “Why Fencers Hate Nick Evangelista.” I take great pride in this. Not that I go out of my way to offend or provoke anyone. I can only offer in my defense that I always say what I believe to be true. Hence, I do not retreat from what I write, nor do I offer my words from the safety of anonymity.

Winston Churchill was once approached by someone who was complaining that he was being attacked in public for his beliefs. Churchill replied, “So, you have enemies. Good. That means you stand for something.” I would say I have a writing history that has always stood for something. If someone wants to hear sportie chatter or classical anachronisms, they should avoid me.

Here are some of my thoughts on various fencing-related topics, some of them autobiographical, some not.

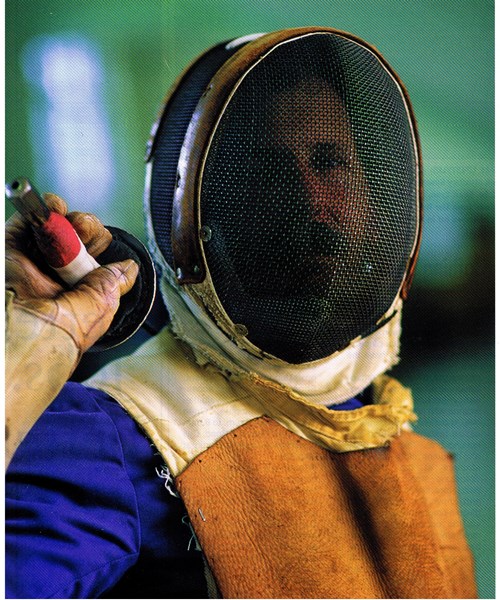

Fencing and Me

When I was growing up in the 1950s, fencing always seemed to be in front of me. In movies and on TV, and in books, sometimes comic books. When I was around 14 years old, The Three Musketeers was my favorite novel. Any and everything with swords got my attention. Fencing seemed so exotic and otherworldly. I thought it was the most amazing thing in the world, and I wanted to learn how to do it. I didn’t have any idea how this would come about—I didn’t know any fencers, or where there were any fencing schools--but somewhere in the back of my brain, I had a feeling I would one day fence. In the end, many things conspired to lead me to fencing. Actually, I sometimes think fencing chose me rather than the other way around. I should add, though, that it was not an easy union. I had to work hard for everything I’ve accomplished.

Fencing Injuries: Personal and Otherwise

In all the years I have been fencing, I have never had a serious injury. Nothing beyond the normal bruises, welts and scrapes one encounters during the day to day of bouting. When I was learning to fence, I was taught balance, timing, and distance. Form was stressed: bent knees to lower one’s center of gravity, the use of the back arm as a counter-balance, the placement of the feet. Basically, I was taught to control my actions. You don’t get hurt when you have control over your actions. Nor do you hurt others.

My background is a traditional fencing game. Falcon Studios was peppered with successful fencers, from former Olympians to local champions. No one gave an inch. Everyone fenced hard. It was very competitive. When you were bouting, the only thing your opponent wanted to teach you was that they were better than you. But it was fencing, not the running, poking school of bipedal jousting. The fencing I learned is the same fencing I teach to my students, and in 43 years of transforming everyday people into fencing people, I have never had a student injured beyond the aforementioned bruises, welts, and scrapes.

On the other hand, I have been injured by everyday life. Broken body parts, and the like. And I have most certainly had to adapt my fencing to these hurdles. One of my most challenging injuries was having my right hand—my fencing hand—crushed in a car door twelve or so years ago. I remember the sound of crunching celery as my metacarpals were being reduced to puzzle pieces. How did I deal with this intrusion to my fencing? Actually, I just kept teaching, because my fingers weren’t broken, and that’s all I needed to maneuver my foil. With every personal injury I’ve had, I just keep teaching, adapting to the situation, until I heal up. Fencing is what I do. Of course, I do not recommend this regimen to anyone else. Today, for me, old injuries regularly suggest impending bad weather.

Outside my own fencing sphere of influence, the injuries I see most in modern fencing are to the knees and ankles. To me, whatever the level of the fencer injured, these problems imply poor training, a fencer lacking proper balance. For all outcries to the contrary, there is something to be said for good, old-fashioned fencing form: an attack with a straight arm, measured foot work, timing flowing from the fingers, the free arm being employed for balance. No silly leaping, no over-extended lunges, no toe-to-toe jabbing, no feet going in ten directions at once. It doesn’t surprise me that so many fencers are being injured in the modern fencing world. The only place where chaos turns into order is on page one of the Bible. Everywhere else, it leads to serious problems.

My Writing

My last book was published in 2001. At the same time, I was both the Fencing History editor for Encyclopedia Britannica, and the publisher of Fencers Quarterly Magazine. Since then, I have gone to college, earned a BA in History, and am now on the verge of my Master’s in History. Lots of writing there, but on topics dictated by educational requirements. More fencing books? I have at least five in my head. Plus, I have my website, where I can pursue short term fencing ideas that interest me. I have a number of options, but I need to get my Master’s Degree out of the way first. It hangs like an albatross around my neck.

Pistol Grips/French Grips

People have commented –often in a derisive fashion--on my dislike of pistol grips. There is a reason why I don’t like them. They are totally incompatible with the requirements of traditional French fencing techniques. The pistol design promotes a heavy-handed style of play that clashes with French subtleties. I tried letting students use pistol grip weapons early on in my teaching career, but it was like trying to mix water and oil, and more oil. It was an impossible mixture. As for the French grip, it has, over the years, fulfilled my notions of what Fencing should be…for me.

Today, my students use only French weapons.

I should also mention--for those who are too young to remember the 1980s--that the Federation Internationale d’Escrime (F.I.E.), the world fencing body, recommended in 1982 that pistol grips be banned from fencing as extremely dangerous. This pronouncement, issued by the F.I.E. medical board, stemmed from some well-publicized fencer deaths. It had to do with the unrelenting, vice-like grip produced by the pistol design. When a blade broke, it did not snap harmlessly away from the target, it punched directly forward into whatever was in front of it. If a blade broke with a sharp angle, that was a real problem. But, because of the uproar this suggestion of exile generated among pistol grip users around the planet—coaches blaming accidents on bad officiating--the F.I.E. instead began issuing equipment requirements to offset and withstand the life threatening potential of said engines doom. If you have ever wondered why there is an “F.I.E. seal of approval” on some pieces of fencing gear, this is where it came from. (For those who prefer historical fact to hysterical denials, I recommend that you read, “A Propos d’un Accident,” by Raoul Clery, American Fencing, Volume 35, No. 1 and 2, 1983.)

Ultimately, pistol grippers, sporties, whoever, can do whatever they want. I really don’t care. I’d just like to warn as many potential fencers away from the p. trap as possible. Official fencing sites on line can explain why fencers—probably all of them—hate me. It won’t change what I know to be true. I grew up in fencing’s Cretaceous Period, right before the scoring box proliferated beyond tournaments--crashing headlong into everyday fencing to become a substitute for brains--and wiped out all rational, intelligent thought on organized fencing strips.

When I was first learning to lunge and parry, almost everyone fenced with French weapons. It wasn’t mindless consensus, it is what worked amazingly well. A few old-timers still showed up at tournaments proudly toting the tools of the Italian school. That always brought up questions like, “Where’d you learn Italian?” As for pistol grips in the early 70s, they were not the ubiquitous items they are today. More common in European circles, they were still an oddity to many American eyes. But things were changing. By the 80s, there was a saying in vogue to justify major, confusing changes on U.S. fencing strips: That’s the way they do it in Europe. The Soviet Union had long embraced the pistol grip, and found they could dominate the scoring box by force. We might describe this as, anything for a touch. Karl Marx would have said, the end justifies the means.

Amid all this sportified politics of the fencing world, I have stayed with my French weapons for almost 48 years. If I could find something better, I would use it. But I have not. I actually used a Belgian pistol grip in a tournament once while my foil was being repaired by the armorer. I won with it, but it felt as foreign to me as a crowbar. I have always relished the calm feel of a French grip slipping easily into my hand. After a while it becomes part of you, an extension of your nervous system. It does take a while to learn to manipulate it from the fingertips. The mastery of anything is never easy. But once you do, fencing stops being a mundane, forceful accumulation of touches, and becomes a game of surprising possibilities. Words like precision, economy of motion, maneuverability, creativity, point control come to mind. The French call the finger play derived from their grip, doighte (pronounced, “dwah”). Anything less, to me, seems like a grand waste of time, shouting “champions” amid electric impulses, medals and all.

My Fencing Regimen Today

I have not competed since the 70s. My business is teaching. My fencing master once said to me, “You can be a great teacher or a great fencer, but you can’t do both at the same time.” I teach because that is what I enjoy the most. But I do fence with all my students who have graduated to bouting. I fence with students who come to me from other salles, as well. I do not hold myself aloof from the world. And, yes, I fence hard. You never let anyone win. Acting as a brick wall is the only way to pull the best out of a student. Anything less than that is a lie, and gives the student a false sense of confidence. They have to earn their touches. Mastery is forged in opposition. Skill is earned under fire. I learned this at Falcon Studios more years ago than I care to remember.

My Training Aids

I think what helps my students the most is continual one-on-one lessons with me, which includes mechanical training and regular bouting. There is always a continual dialogue that runs through these sessions, which allows the student to apply critical thinking to his or her situation. My ultimate goal is to produce creative, independent fencers, who can easily function in any fencing situation without my assistance.

I also employ aspects of Behavioral Psychology in my teaching. Let’s face it, when you teach someone to fence, you are obviously attempting to modify their behavior, inserting the good, expunging the bad. If you know specific behavioral techniques, this can make the procedure much easier. When I was an undergrad in college, and minoring in Psych, I wrote a 56 page study on the use of behavioral techniques in training fencing students. They do work.

If someone reading this is thinking, “What about cross-training?” I am not a big fan of cross-training. I believe that the best training for fencing is fencing. Lots of fencing. To practice fencing effectively, you need active human opposition to overcome. Everything else is everything else.

Choosing a Weapon

This is my recipe for knowing which weapon is for you:

Start with foil, and fence it for a year. Foil will teach you the fundamentals of fencing thought and behavior, which are embedded in its conventions. Year two: add epee, which will hone your timing, point control, and judgement. During this time, shift between epee and foil. Year three: Add sabre. Sabre always comes last. It is the most divergent from the other two weapons. But, here, you can easily integrate the point control of foil and epee into sabre. In this third year, fence all three weapons. At the end of the third year, you will not only have a solid grounding in each discipline, but you will also know which weapon speaks the loudest to you. Unfortunately, many students coming to fencing want instant gratification, and immediately pick the weapon that seems the coolest to them, and many coaches will let them do this.

French School versus Italian

The two traditional schools of fencing are the Italian and French. The Italians began developing systematic fencing systems first during the early 16th century. This, to take the place of armor that was being abandoned in the wake of firearms. The French became serious about establishing their own approach to fencing during the 17th century, chiefly because they liked neither Italian fencing masters, nor their theories of swordplay.

Although today there are structural similarities between the two fighting systems--the Italians having borrowed from the French at the end of the 19th century to establish a more cohesive method of operation--the philosophies of the two remain widely separated by temperament. The Italian system primarily stresses the dynamics of strength, speed, and aggressive manipulation. To physically dominate opposition is its goal. The French approach, on the other hand, is built on finesse, economy of motion, and strategy. The well-versed French fencer looks for ways around his opponent’s strengths, rather than meeting them head-on. To my way of thinking, this makes the French school more flexible and creative than the Italian, which tends to be more dogmatic. I might also add that the French school, with its non-confrontational approach, easily fits a wider range of physical types and demeanors. This means, you do not have to be the strongest, fastest, or most aggressive fencer in town to win.

The Point d’Arret

The question of the value of the point d’arret sometimes come up. When you have the proper spirit and training, fencing is fencing. The best fencing is an internal expression. What does using that sharp little crown of thorns say about the person using it? I’m a serious fencer? Sport fencers can’t make fun of me? My soul was forged on a bed of nails? As far as I’m concerned, the point d’arret is a “classical” affectation. Period. It is no more necessary to excellent fencing than scoring boxes.

My Favorite Movie Duels

I am often asked about fencing in the movies. My fencing master, Ralph Faulkner, was known as “the Fencing Master to the Stars.” He worked with all the greats during Hollywood’s Golden Age: Errol Flynn, Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., Ronald Coleman, and Basil Rathbone. I worked with many actors when I lived and taught fencing in Southern California. I have written about films with fencing in them. It is expected that I know something about swashbuckler films.

My favorite movie duel of all time is from the 1940 Mark of Zorro, between Tyrone Power and Basil Rathbone. To me, it is the most balanced and cleanly executed sword fight ever produced. Also, it is carried out without any background music, something of a rarity in filmed action. But you don’t really notice this lack, because the sharp ring and changing tempo of the clashing blades more than fills the gap. It is a wonderful sword fight.

Runner up: The final duel between Errol Flynn and Basil Rathbone in The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938). If the Zorro duel didn’t exist, I would pick this one. In all other aspects, I think Robin Hood is the superior film.

One more plug: I also recommend the fencing in the French movie, On Guard. It is one of the best modern swashbuckler films I know of. All the sword fights are superior, the story, based on an 1858 French novel, is interesting, and it even has a wonderful, though anatomically flawed, secret thrust. A good movie to own a copy of.