Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night

Nick Evangelista

Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night

By Nick Evangelista

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

-- Dylan Thomas

A remarkable feature of fencing is that it appears to imbue a long and fruitful life onto the active fencer. That is, barring catastrophic intervention. For instance, there was famed Hungarian master Laszlo Borsody, who was killed in a pistol duel; American fencing champion and Olympian George Calnan, who was killed in a dirigible crash; and the French fencing master Augustine Rousseau, who was guillotined during the French Revolution. The rewards of fencing could do nothing to waylay these unhappy demises. Yet, all things being equal, for those of us not destined to be run over by school buses, hit by meteorites, or eaten by Amazon army ants, there is, through the application of fencing, hope for a lucid and productive antiquity.

There is much circumstantial evidence in the form of very old active fencers and fencing masters to suggest that fencing, if not the fountain of youth, is at least a fountain of not-dead-and-hanging-in-there. We can look back through fencing’s extensive history for numerous examples of the active senior fencer and master.

Sixteenth Century

Maestro Achille Marozzo, fencing master, the first author of note with regard to a unified sword fighting theory, lived well into advanced age, dying in 1553, at the age of 69, Nineteenth century writer Egerton Castle alludes to this fact in his Schools and Masters of Fence (1885), when writing about another famed master, Salvator Fabris. “Fabris was born in Padua in 1544, and began his profession of arms when Marozzo was teaching in his old age.” In a time of plagues, nonexistent hygiene, and poor dietary practices—not to mention an ever-present opportunity for a quick death on some dark Renaissance avenue—Marozzo’s advanced age was a testament to a robust life following the sword.

Ridolfo Capo Ferro, sometimes known as “the Grandfather of Modern Fencing,” was the leading fencing master of the city state of Siena, in what is now north central Italy. Capo Ferro’s treatise on rapier combat, Gran Simulacro dell’arte e dell’uso della Scherma, publish in 1610, fixed many concepts of present day fencing, such as the lunge, into standard practice. Although little is known biographically of Ridolfo beyond his location and his vocation, we can infer from the portrait of him appearing in his book, that he was a no-nonsense, sturdy, proud man. His age in the 1610 illustration has been set roughly at 52 years, a laudable number of years in such a violent profession. His age when he died has proven rather elusive.

Seventeenth Century

The Great Figg

Fencing master and gladiator James Figg, known as the Atlas of the Sword, was a dynamic individual well into his last days. He was the leading prize-fighter of his day, participating in nearly three hundred public contests of sword skill for money. It was said of him, even in his old age, “In him, Strength, Resolution, and unparalleled Judgement conspired to make a matchless master.” When public exhibitions of sword fighting lost favor in the public’s eye, Figg took up pugilism to earn his daily bread.

Donald McBane, a crusty contemporary of James Figg—with a hard life as a soldier, swordsman, and pimp under his belt (and a silver plate in his head)—went on at the age of 50 to become an illustrious prize-fighter. In all, he fought in thirty-seven matches. In his last public appearance, at the age of 63, he thoroughly defeated an opponent a fraction of his age, giving him several severe wounds and breaking his arm. This contest was later immortalized in a ballad. McBane then went on to write a book, The Expert Swordman’s Companion, which doubled as an autobiography and fencing manual.

Eighteenth Century

Domenico Angelo

Domenico Angelo was the most renowned fencing master of the eighteenth century. In this position, he was the first to insist that fencing had a life beyond a martial art as an adjunct to a healthful and cultured life, opening the door to the recognition of fencing as a sport. His book, L’Ecole des Armes (1763)—republished in 1765 and 1767 as The School of Fencing, and then again in 1787 and 1799 in a redesigned edition—is arguably the most celebrated fencing manual of all time. It has been reported that Angelo taught until a few days before his death at the age of 86. In his wake, he also established a fencing dynasty that lasted for 150 years.

Spy, fencer, and transvestite, the Chevalier d’Eon lived to the age of 82. At the age of 60, he engaged in a celebrated fencing match with the famous swordsman, the Chevalier Saint-Georges, who, at the time, was a third his age. Despite being hampered by wearing a dress, d’Eon scored seven strong touches against his much younger opponent.

Henry Angelo, known as Harry, Domenico’s only son, and a successful fencing master like his father, died at the age of 82, after a productive life of teaching fencing. In his latter years, more than any other fencing master, including his father, Harry single-handedly set out to popularize fencing as a sport in England. His small book, with the big title, A treatise on the utility and advantages of fencing, giving the opinions of the most eminent Authors and Medical Practitioners on the important advantages derived from a knowledge of the Art as a means of self defence, and a promoter of health, illustrated by forty-seven engravings (1817), is a testament to his aggressive efforts to bring fencing to the masses.

Nineteenth Century

Jean-Louis Michel, known throughout his life simply as Jean-Louis, was one of France’s greatest fencers and one of its deadliest duelists of the 19th century. As an orphaned child of racially mixed heritage, he enlisted in the French army at the age of 11, and was, in time, because he showed an immediate affinity for it, trained vigorously in the art of fencing. By the time he was an adult, he was a master of the art, and there are many stories of his exploits. Over the years, he taught the art of the sword both in the army and privately. In his old age, with cataracts on both of his eyes, he continued to teach by touch alone. He died at the age of 80.

Modern Olympics founder Baron Pierre de Coubertin was an avid fencer for much of his life. He, more than anyone else, made sure fencing was included in the first Olympic Games in 1896. The baron, a perpetually vigorous man, died at the age of 73.

Egerton Castle

Author and avid fencer Egerton Castle led an active and creative life, dying at the age of 62. He wrote the much-lauded Schools and Masters of Fence (1885), perhaps the greatest fencing history ever produced. He also wrote numerous romantic novels with his wife.

A fencer from the time of his youth, Sir Richard Francis Burton wrote the scholarly anthropological study, The Book of the Sword (1884), and The Sentiment of the Sword (1911). A prolific author, he also penned his own translations of the Arabian Nights and The Kama Sutra, plus many other books. Burton, who was also a soldier and explorer, said towards the end of his days, “Fencing was the great solace of my life.” He was 69 when he died.

French fencing master Baptiste Bertrand was the most successful teacher of fencing in Victorian London. Moreover, he was the principal arranger of theatrical sword duels for the stage. He also championed fencing for women, at a time when it was still entrenched as a “men only” sport. And, like Domenico Angelo before him, he founded a dynasty of fencing masters that survived for generations. Bertrand, active and teaching to the end of his life, died in his late 70s.

Alfred Hutton, soldier, writer, antiquarian and swordsman, helped to orchestrate the first English revival of historical fencing in the late nineteenth century. He also wrote a number of fencing-related books. He was active in fencing until his death at the age of 71.

Twentieth Century and into the Twenty-first Century

Regarded as one of the legends of modern fencing, Cuban Ramon Fonst won gold medals in the Olympics of 1900 and 1904. Beginning his winning ways internationally at the age of 16, he was still reckoned a formidable fencer late in life. He died at the age of 75.

The great Spanish master Julio Castello, involved in fencing his whole life, died at 91. Although old age slowed him down in later years, his interest in the development of young fencers never flagged. Almost to the end, cane in hand, he could be found surveying classes taught by his former students.

Giorgio Santelli

Giorgio Santelli, fencing master, duelist, and five-time U.S. Olympic fencing coach, started fencing at the age of 6, and never retired. He was 88 when he died. A few years before his death in 1985, Santelli once noted, “Being my age, I cannot move very fast anymore. But the moment I put a foil in my hand, I start to move. I get a kick seeing myself hopping around.”

Italo Santelli, the father of Giorgio Santelli, was one of the greatest of modern fencing masters. He is credited with bringing various fencing styles into a single method, which, by the end of the nineteenth century placed the Italians among the best swordsmen in Europe. Then, in 1896, he was asked by the Hungarian government to develop fencing in that country. He agreed, establishing the foundation of the Hungarian school of sabre fencing, which produced the most successful sabre fencers of the twentieth century. Santelli taught in Budapest for almost fifty years, and was knighted by the Hungarian for his efforts. Italo was 74 when he died.

Beppe Nadi, lifelong fencing master, and father of champion fencers Nedo and Aldo Nadi, died at the age of 84.

Hungary produced a number of long-lived fencing masters. Lajos Csiszar was over 90 when he died. Odon Niedekichner died at the age of 82; and Casaba Elthes, at 83. Maestro Elthes once observed, “A good coach is like a good priest. He study until he die.”

Well-known German fencing master Hans Halberstadt, coach of the greatest woman fencer of all-time, Helena Mayer, died at 82.

Henri Uyttenhove

A fencer for most of his life, Henri Uyttenhove was the first fencing master ever to be hired to direct swordfights in movies. His work included the Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. classics, The Mark of Zorro (1920), The Three Musketeers (1921), and Robin Hood (1922). A well-respected master in the sport world, he also taught fencing for the Los Angeles Athletic Club; and, later, on a collegiate level for USC and UCLA. Privately, he maintained his own school in Pasadena, CA. Uyttenhove died in 1950, at the age of 73.

Fred Cavens, fencing master at the age of 21, went on to a career as a movie fencing coach and fight arranger in Hollywood, putting together swordplay for films like The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), The Sea Hawk (1940), and The Mark of Zorro (1940). Cavens kept active and working almost up to the end of his life, his last job being the 1950s Disney Zorro television series. He died at 72.

Fencing coach Julia Jones Pugliese, founder of the National Intercollegiate Women’s Fencing Association, and never far from fencing, died at the age of 84.

Maestro William Gaugler established the first fencing master training course–the Military Fencing Master’s Program—in the United States, in 1979. This program is credited with revitalizing the traditional Italian School of fencing when it was at its lowest ebb in America. Not only did Gaugler teach fencing, but he fenced well into his 70s. He was also a much respected Archaeologist and author. He died at the age of 80.

Fencing Master Bob Anderson, former British Olympian fencer and fight arranger, who was responsible for celebrated swordfights in movies like The Princess Bride (1987), The Mask of Zorro (1998), and the Lord of the Rings (2003), was active in the theatrical fencing world almost until the time of his death, at the age of 89, in 2012.

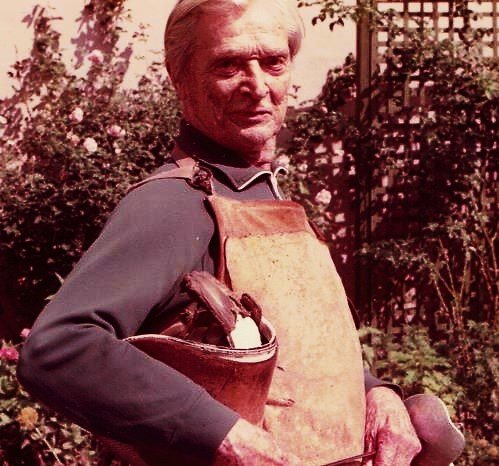

Ralph Faulkner

Lastly, I look to my own fencing master, Ralph Faulkner. A member of two Olympic teams (1928 and 1932), and a movie fencing coach, Faulkner never relinquished his hold on fencing. At times, it almost seemed like he would live forever. During the 1984 Olympics, he was officially touted as the World’s Oldest Living Olympian, and he spent long hours as a fund-raiser for the U.S. Olympic Committee. He was 92 years old at the time. He just went on and on and on. In fact, he taught right up to a few weeks before he died of a stroke at the age of 95 and ½, with 64 years of fencing under his belt. Faulkner once said of his life in fencing, “How can you retire from something you love? When you do that, you might as well be dead.”

The list of long-lived fencers, of course, doesn’t end here. I have only hit on a few examples. With some extensive research, I could doubtlessly write a book.

Finally

Anyway, in closing this essay, I will add one more tidbit to the mixture of fencing and longevity: my own personal experience as a fencer. After all, this is what sparked my interest in the fencing/age issue in the first place.

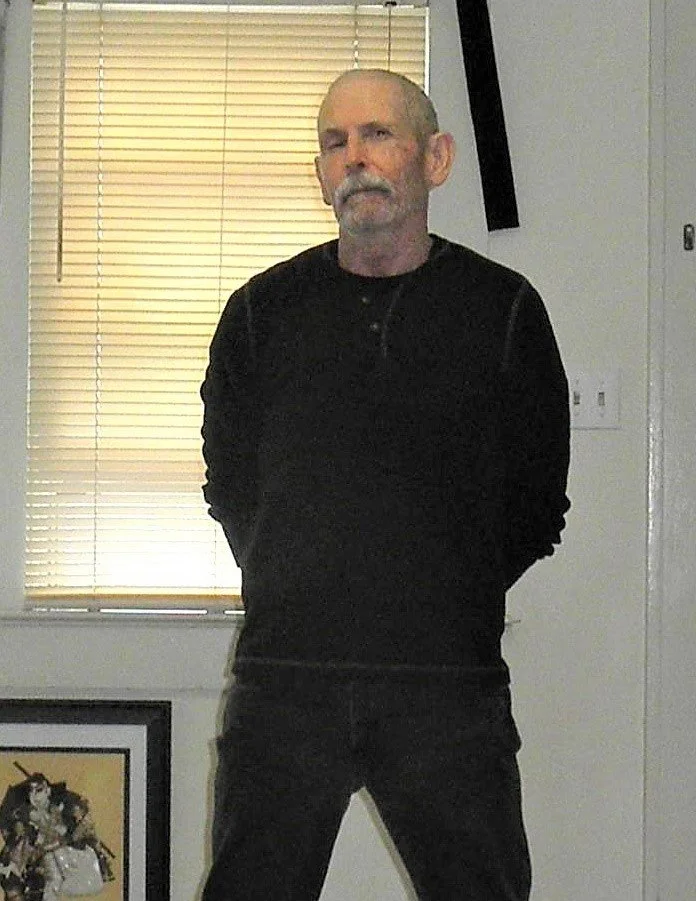

Nick Evangelista

After 51 years of continual fencing, at the age of 72, I find myself in the surprising position of being a senior citizen. But I do not feel like a senior citizen, nor do I think of myself as one, even though the Social Security Administration and Medicare have labeled me as such. I teach fencing, and I fence with my students daily, without hesitation. It is surprising to many of those I teach to find out how old I am. One of my kid students announced, upon learning my age, “You’re older than my grandmother!” I told her, “I always take off my mummy wrappings when I teach, so I don’t trip over them, and break a hip.” Last week, I took a 14 mile walk, just because I was having a slow teaching week due to inclement winter weather, and thought I needed some extra exercise. My blood pressure is generally around 110 over 60. And I have weighed 150 pounds for the last 17 years, without dieting. And not so long also, after a physical checkup by my doctor, he announced happily that he thought I’d most likely live forever--unless I got run over by a pick-up truck. I promised to wear my glasses when crossing streets. So, basically, going into my so-called old age, I am in good shape for any age. By the way, I plan on being the first 100-year-old active fencing master. That’ll be one for the Guinness Book of World Records. I only have twenty-eight years to go!

Cognitively, I might add, I am still thinking the useful thoughts. Everyday single day of my life, I have to illuminate the whys and wherefores of fencing for students. I pride myself in being able to explain everything I teach, and why I teach it. I enjoy being put on the spot with questions. Why this, and not this? What does this mean? Where did this come from? Said the Greek philosopher Pericles, “One who forms judgement on any point but cannot explain it clearly might as well never have thought at all on the subject.” I believe in this statement emphatically.

To me, there is no life without the mind, and no mind without life. I have long advocated the idea that the real game of fencing goes on between the brain and the hand. It is a subtle blend of the mental and physical. And herein lies the issue of fencing and longevity. More and more, medical science is finding how the physical and the mental interact and support or hinder one another on a deep cellular level.

Fencing, then, as I see it, is one of those activities that create a powerful bond with the world, promoting health for both the body and the mind through its endless and varied challenges. Each new opponent connects us to the moment. Every attack and every parry demands our best, and tests our will. Is it any wonder fencing and old age go together? We have no choice, as long as we live, but to keep tacking birthdays onto our resume; but fencing, in its magical demand for our attention, our resolve, our ingenuity, and all our physical possibilities, keeps giving us new pages to write our story on.

In fencing, we have a stepping stone to a life of passion and experience, of creation and challenge. Certainly, in the world, there are many routes to this end. But in fencing, we also find a remedy for old age. In the end, who wants to slip quietly from existence, when you can go out to the sound of clashing swords?

Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night

By Dylan Thomas

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.