This is not a fiction, a parable, or a flight of fancy a la Alexandre Dumas. As is the case with much of my fencing writing, it has been wrung from my own personal experience, sometimes with much discomfort. I serve myself up as both good and bad examples, mainly because fencing is made up of good and bad experiences. How we adjust to these will determine our fencing future.

The following was an important event for me, a life defining moment. I offer it to the odd reader with the hope that it inspires someone to regard fencing, not simply as a game of acquiring touches, but as a method of adding to their personal growth as a Homo sapiens. In this sometimes-impersonal world of technology and artificial--and often remote--stimulation, we need all the human input we can get. Life is about experiencing life in our face. The Romans had a saying, Magnae res non fiunt sine periculo. That is, Great things are not accomplished without danger. Real, real, real life is a challenge, rightly sometimes tagged, a pisser!

Here, then, is my story:

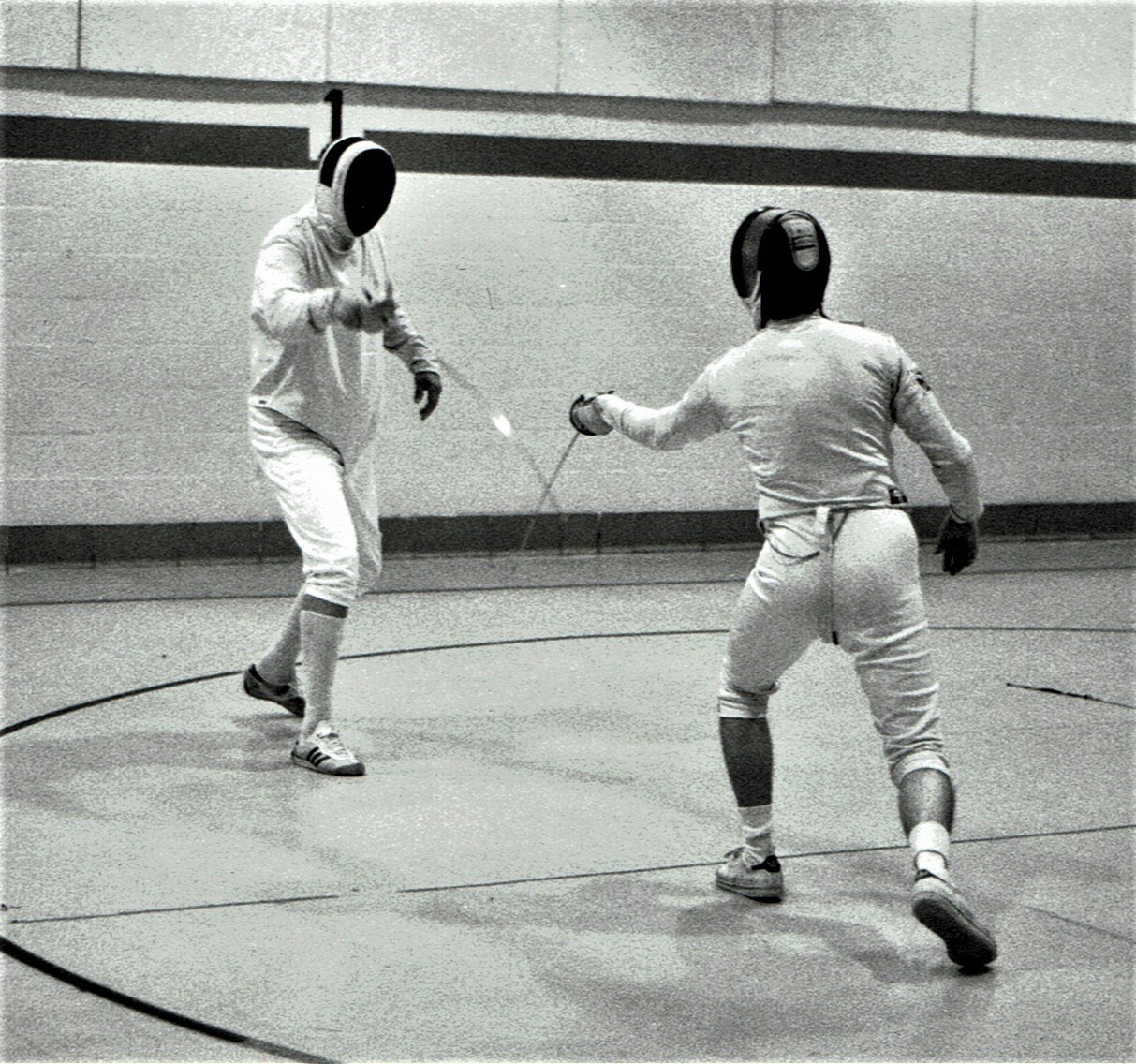

As I made a speedy retreat down the fencing strip, my opponent’s foil point, bobbing and weaving rhythmically high in the air, kept pace with me step for step. There was no escape. Suddenly it shot out and downward, slamming against my sternum with the unyielding force of a stove poker. Despite the protective layers of a padded fencing jacket, pain exploded in my chest. A hollow shriek from the electric scoring machine off to one side taunted me. “Red light. Touch right!” the bout director shouted, pointing an accusing finger at me. “The score is One to zero.”

I stood there staring at the floor, groaning into my fencing mask. With my free hand I rubbed the spot where I’d been hit, the hurt lingering like an echo. I did my best to smooth out the rumple on my lame vest where the attacking blade had left a neat little crater. Gripping my electric French foil in my damp, chamois-gloved right hand, I fell into a weary on-guard position. I was doomed! There, maybe twelve feet away on the narrow fencing strip, loomed a World Professional Fencing Champion, confident and without mercy. I closed my eyes for a long moment, in a vain attempt to block out his overpowering presence. But there was no place to hide….

The evening had begun innocently enough. The great room where we fenced—as wide and deep as an airplane hangar—was thrown open to the friendly sounds and smells of the warm Hollywood summer night. The hall was filled with fencers, some sitting around chatting, some practicing footwork in front of the room’s full-length mirror, some bouting vigorously. The loud click-clack of contradicting blades perforated the evening’s otherwise unhurried embrace.

The Maestro, Ralph Faulkner, the Boss as he was affectionately called--former Olympian and movie fencing master--was at his regular teaching spot next to the ancient, cracked blackboard where the day’s students were listed. I was teaching, ensconced in my usual spot off to one side of the room. After years of study and apprenticeship, and a happy stint of fencing my way around Europe, I had been made the old master’s assistant at the famous Falcon Studios fencing salle. The Boss thought highly of me. I had become heir to his rich fencing knowledge, the one student chosen out of all his students to carry on the tradition of his traditional teaching style and thought.

Often, I would be working with students for six hours at a stretch---sometimes longer—with almost no breaks between lessons. Then, teaching became an exercise in endurance. I taught until I was done. But on this evening lessons zoomed by, and I found I had some time for bouting. I congratulated myself on my good fortune. It wasn’t often I had free fencing time. I had absolutely no inkling of what was to come.

I began working out with a student on the school’s antique electric scoring machine. It was a giant device, housed in a large, black leather carrying case. When it was opened, with its dials and gauges, it looked like something a traveling executioner might tote around to carry out freelance electrocutions. The student and I would fence a few touches. Then, we’d discuss this attack or that defensive move. Nothing terribly competitive, just fun, with a bit of learning thrown in.

I was so intent upon what we were doing, I never noticed when He arrived. The Champion. But suddenly, he was there, hovering, watching, staring at me, through me. I sensed his presence and looked over. He dropped his fencing bag like a dead body, striding purposefully toward me. Without hesitating, or offered greeting, he stopped a few feet away from me. I looked over at him, and said hello to be polite “Nicky, we must fence now,” he said emphatically, never taking his eyes off me. There was no hint of please in his voice or manner. It was a demand, not a request, a demand to be obeyed. No way out. I nodded. Fencing etiquette compelled me to agree.

I immediately felt a wave of anxiety flow over me. I didn’t want to face the Champion, not now, or ever. I knew why he was here on this particular evening. He was after me. And this was no paranoid delusion. At one time or another, since he had come to Southern California from Europe—where he had been a successful master—he made it a practice to fence with and beat every fencer who showed up at our school. Experienced, inexperienced, it didn’t matter. It wasn’t enough that he was an acknowledged champion of his profession, he had to show everyone he was their superior. With this fact in mind, thus far, I was the only one left who had escaped his indomitable onslaught. I was keenly aware of this, and obviously so was he. Up to this point, by always being busy with teaching, I had been spared the “privilege” of being publicly thrashed by this god of fencing. That grievous oversight was about to be rectified.

The Champion was a world-class competitor, ranked number one in the world as a professional fencer in sabre and number five in foil. He was a fencer with few rivals. But, for him, this fact couldn’t simply be understood or implied, it had to be demonstrated forcefully to all concerned. The Champion couldn't fence with Mr. Faulkner, because the Boss was in his 80s. Besides, challenging a fencing master in his own domain would have been a breach of fencing tradition. I, on the other hand, as Maestro Faulkner’s protégé, was not covered by any such convention. In a way, the Universe had volunteered me. I was the symbol of everything the Faulkner School of Fencing stood for. I was also the final obstacle to the Champion’s adamant statement of complete superiority. He had to make certain that all the denizens of Falcon--but especially the Boss and me--clearly understood I was his inferior. It wasn’t just a bout, it was conquering the Faulkner School of Fencing, including Mr. Faulkner, forever. If there was to be peace in Falcon Studios, it must be a Carthaginian Peace. Totally destruction, not a creature or blade of grass left standing. The proving, however, was something I would rather have not faced in this lifetime.

To be honest, I was aware that I’d been dodging the Champion for some time. Maybe not overtly. But I always felt secure in my industry. My teaching was my armor. And that was the crux of the matter. I was a teacher, after all. I worked with every student that came to our school. I had given most of them their introduction to fencing. I had achieved a position of authority and respect. These people believed I knew something. What would they think if I was ground into atoms right in front of them? And this was clearly the fate that one person in the world was anticipating for me. The Champion wanted to crush me and all signs of my ability as a fencer. I knew everyone would be expecting me to hold my own with him, but I personally doubted that I could. The entire school, and the Boss, would then be a witness to my mediocrity. I think to be exposed for our weaknesses in a public arena is everyone’s fear. Still, even the Catholic Church, with its emphasis on soul cleansing confessions, allows for private disclosure of one's failings. But here I was about to be stripped naked publicly, my fencing defects, whatever they might be, revealed to the world. I didn’t want to lose what had taken me years to build up. This was my life. It was also, in a way, the life of Falcon.

But by purposefully seeking me out this day, the Champion had brought the matter to a head. He had thrown down the gauntlet, a challenge as meaningful as any issued in the heyday of dueling. A duel is a duel if you have something to lose. Be it reputation, money, possessions, or life. If I said I was too tired, or too busy, or too anything, it would have been clear I was backing down. I was trapped. Not fencing would have been more humiliating than being creamed on the fencing strip. I wondered how the Champion knew I’d be free this evening. He had fencing acquaintances at Falcon. Had someone tipped him off? Panic makes you think strange thoughts. Most likely it just was. Just time on the Cosmic time clock. Dinosaurs. The Fall of the Roman Empire. The Spanish Inquisition. The French Revolution. Me.

Using the electric scoring machine made the meeting even more convenient for the Champion. Modern competition fencing weapons are wired to score touches electronically. Both fencers are hooked up, via extension cords, to a piece of machinery that both detects and announces when a blade has made contact on an opponent, on target or off. There is a small depressible button on the end of the blade. When it is pushed in fully by contact, it establishes an electrical connection that triggers the box. It is not unlike pressing a doorbell. For fencers, it’s ding-dong, your dead, metaphorically speaking. With the box’s flashing lights and blaring buzzer, there would be no doubt when a touch had been scored. One, two, three, four, five touches! Bout over. Everyone would know I had hit the fan.

As I waited for the Champion to suit up, I did my best to bolster my resolve. After all, I might not lose badly. I reminded myself I was a very good fencer. But, but, but I was not the Champion. The Champion was six feet, four inches tall, and two hundred, twenty muscular pounds of lightning responses. Furthermore, he had been trained and molded in Europe’s best salles, from a very early age, into a polished fighting machine. The Champion was ranked among the finest fencers the modern world had produced. I, on the other hand, was five feet, eight inches tall, one hundred, thirty pounds, had been fencing for almost six years, and, most definitely, I was not the Champion. There was not a lot of buttressing I could do with my starkly uninspiring facts.

I suddenly felt the borders of the fencing strip closing in on me. Forty feet long, six feet wide. It didn’t seem like much room to maneuver in. And as the Champion approached, his reach resembling an extension bridge, the maneuvering space seemed to grow smaller by the second. I was thinking a football field would have been worth a lot of money about now. People, I noticed uneasily, were already drifting over to watch the carnage. An anonymous encounter was out of the question.

The Champion slowly attached the cords that connected him to the electrical circuit we were now sharing. “Are you ready, Nicky?” he said amiably, his voice full of a mocking self-assurance that told me I had already lost the day I was born. He was saying to me, in his own professional way, he could make it a thousand touches to zero if he wanted to. He really wanted to rub it in. I had, for him, escaped my fate for far too long. “I’m ready,” I replied, my stomach flopping over. I ground my teeth together to keep them from chattering.

Then, it was time to begin….

The first touch had been delivered. I stood there reliving it over and over in my mind, taking it in like some kind of penance. The explosion down the fencing strip, a freight train caught in a tornado, the attacking blade whipping through the air like a swarm of bees, the touch hitting like a meteor strike. The Champion knew what he was doing. A warning of things to come. Intimidation is a proven negotiating tool. I folded inward. I cannot beat this man. I cannot beat him. He can’t be stopped.

Then, suddenly, out of nowhere, there was a pause in the eye of my storm. Something inside me, my inner compass, spun around. This wasn't what fencing was about. I stepped back and shook my head, realizing what I was doing. My negativity was a slap in the face. Wait a minute. I’m not approaching this like a fencer. I’m giving in to an idea, a preconceived notion. I’m not just being beaten; I’m fashioning my own downfall.

That provoking jab of the Champion’s foil blade into my reality, meant to put fear into me, had done me a service. It snapped me out of my despair and made me start thinking. There was no point in dwelling on the outcome of this encounter. It was going to be whatever it was going to be, whether I worried about it or not. If I was going to accomplish anything, I had to forget about winning and losing. I needed to fill my head with fencer thoughts and get on with the business of fencing the way I’d been taught. I needed a plan. I needed a strategy.

There are four questions to be asked in fencing: What is my opponent doing? How are they doing it? What can I do to counter it? And, finally, Can I do what I’ve chosen to do? What, how, hypothesis, test: these are not only the steppingstones to understanding every opponent in fencing, but they are also the essence of critical thinking, and the foundation of ages-old scientific inquiry. Thinking is ground zero. We are the weapon.

The rest of my life began.

"Fencers ready?"

“Ready.”

“Fence!”

I launched an attack, a one-two. Feint into sixte, deception into quarte. Not as fast or as forceful as the Champion’s onslaught, but well-timed and deliberate. My intent had caught him off guard. He had expected to keep me totally on the defensive. I touched him on the chest. My light blinked green on the scoring box.

"Touch left," said the director, with a hint of surprise in his voice.

Then, I got another touch. A coupé into sixte. That one surprised both of us. Suddenly, I was ahead. Now, I felt loose and ready for action.

Two touches to one.

This was followed by an insane, straining fleche into quarte, and that hit, too. I’d caught him in preparation. Was I fencing? I was fencing! Score: three to one.

But now, the Champion hunkered down, realizing he had underestimated me. Using his powerful footwork to threaten me, he moved forward aggressively, got me to fold and run, instead of thinking strategically. He hit me with the fastest disengage into sixte on the advance I had ever seen. When I finally tried to parry, it was too late. His blade simply pushed mine aside like a straw.

The crowd began to grow on either side of the fencing strip. The bout had become the center attraction at Falcon Studios.

A moment later, I did a coulé-disengage from quarte into the low outside line of seconde. The feint of coulé in the high line masked my true intent. Coulé-disengage, dessus-dessous. I had once been told that no one could watch a well-framed feint of coulé running down their blade without making a forceful parry of opposition, which would then tell you immediately when to derobe off their blade. This was no exaggeration. Even better, the Champion did not know I was familiar with low line actions. I had tried nothing in the low line thus far. Surprise is always a potent factor in fencing.

Four. I was at four touches.

Now, I needed only one more to win.

But the Champion came back with a crushing, unstoppable beat-straight hit. I should have countered with a non-resisting parry to channel his energy away from me. But I’d hesitated for just a second, which caused me to absorb all the power of his beat.

The score was now four to three. The next action came out of nowhere. The Champion launched a muscular disengaged into quarte. More strength. I parried contra de sixte with a croisé. The croisé, a parry and riposte in a single flowing action, with leverage behind it, unknown to many, magically displaced the approaching lightning bolt into empty air. My foil tip and the Champion’s line of sixte met. Physics versus insistence. One light on the scoring box, Green.

I couldn't believe it. I did it. Five touches to three. I won! I really actually truly totally won!

Pause.

Sort of.

Pause.

I thought.

Pause.

The Champion switched to Plan B. Fencing is sometimes called physical chess. So, when your King is cornered, what do you do? The old one abdicates, and you crown another King.

When I extended my free hand to shake his, the Champion stepped back, pulling his hand away. “Nicky, you know we are going for ten touches.”

No, I did not know that. I think this was a bit of improvisation that would never have materialized if the score had been turned around the other way. But what could I say? Liar, liar, liar! Pants on fire! To a world champion fencer? I don't think that would have helped. I just shrugged. My spirits plummeted. This was the end. The Champion had obviously minimized my potential, even more than I had. But now he was surely going to pull out all the stops. He took off his mask for a moment to wipe the sweat from his face. It was a face without humor, a face that was determined and confident of victory. The Champion was thinking of what to write on my tombstone.

But…!

I pulled myself back together. I regrouped my forces. The Champion was messing with my brain again. Just the same, I would not be bullied. No mind games. If he was going to win, he was going to have to out-fence me. I reminded myself I was still in the lead.

The Champion did not get his wish. Over the next few minutes, we traded touch for touch. I had never fenced this well in my life. Letting go of losing, letting go of winning, I just fenced, finding myself, finding my potential.

I brought the score to nine-seven with a quick parry-riposte in quarte. The Champion, I thought, was slowing down a bit.

Déjà vu. Once again, I was one touch away from winning, this time really winning. I could do it. There would be no continuations. Just one touch. But some touches never materialize when you need them. They linger in the air, like the image of the Holy Grail.

Fencers ready?

"Fence!"

Abruptly, the champion lifted my foil tip into high septime with a horizontal flip of his blade, slamming a touch square into my solar plexus. It was meant to hurt more than any of the other touches, not just to shake me up, but to make me afraid. It did. It took me a minute to catch my breath.

The score was nine-eight.

Sweat dappled the ground around the Champion’s feet. His chest heaved, and he tapped the floor impatiently with his foil blade. The crowd pressed closer. Even the Boss had come over to watch the outcome of the match.

The director held up his hand. “Fencers ready?” A slow nod. “Fence!”

The Champion advanced on me with an aggressive burst of speed, his blade waving back and forth menacingly to throw me into a panic. This was his favorite move. He’d used it on me for his first touch. I suddenly realized I had seen him use it repeatedly on other fencers. Based more on sabre actions than foil, it was nevertheless daunting. I realized what he was doing, but I fell into his trap, anyway. Sometimes, just knowing isn't enough. You must feel what you are doing to be in control. I retreated three steps, reacting without thought, my blade beating the air wildly, my body tightening. His previous touch had accomplished the result he wanted. He's sucked me into his trap. He forced me to run away and open my guard. His weapon, shooting out and downward in a deadly arc, found its mark just beneath my sword arm.

I looked down helplessly, shaking my head.

The score was tied: nine touches to nine.

Lungs laboring, I stooped over, my left hand resting on my knee, my foil blade tip on the floor. I thought about the distance I had traveled in my mind since the bout began. From self-styled loser to an opponent with purpose. Now, I was one touch away from actually winning. But so was the Champion. And he was used to winning.

I realized abruptly that I wanted this bout more than anything I had ever wanted before in my life. But it had nothing to do with merely winning or losing. The Champion could beat me, and no one could possibly fault my performance. Even Mr. Faulkner would be pleased with my fencing. It was something else, something that had more to do with who I was. It was about completing the journey and becoming. Becoming what? A real fencer? A real fencer, yes. That was it. With the whole thing boiling down to a single touch, that one touch was all touches for the rest of my life. Could I reach down deep inside myself, and control that which had once mastered me? Could I create, under the greatest pressure of my life, one unknown something that would truly say, this is fencing. Or would I be left at the gate looking in? The fight was not with the Champion but with myself.

The director glanced in my direction. “Are you ready?” I took a deep breath. “Yes.” He looked at the Champion. “Are you ready?” “I am.” This was it. “The score is tied nine to nine, la belle. Fencers ready?" A long, long pause. "Fence!”

I focused with a snap.

Now, there are moments in fencing when ability and true potential intersect, and you transcend your usual approach to technique and strategy; when the veil lifts and the truth of the fencing experience becomes apparent, crystal clear, converging to a fine point of awareness. Where this recognition comes from, I have no idea. But when it descends, it feels like a gift.

For me, it happened here.

I looked at the champion, and instantly I knew what he was going to do. I thought to myself, he’s going to try the same attack he just hit me with. He can’t help himself. I was certain of it. Maybe it was the way he came on guard. Or the way he held his blade. Or the way he shifted his weight to his front leg. I simply knew. It was also his favorite foil attack, and it had just worked extremely well against me. I was obviously susceptible to his bait. I had flinched. I had backed down from this attack twice. It would also be an insult to hit me with the same attack twice in a row. It seemed obvious he would pick this a move to end our bout with.

I also knew if I retreated, as I had before, if I locked into his fanning blade motions, attempting to parry, as I had before, he would have me for sure. I would be fencing his game. His speed and strength would shoot his point right through my defenses, and the bout would be over. No matter how fast or far I retreated, he would follow me to the ends of the earth for that final touch. How satisfying for him.

All this passed through my brain the instant I came on guard. I also knew what I had to do. Yet, I wondered, would I have the self-discipline to carry out my plan? I relaxed, breathing deeply, fighting back a tension that was attempting to wrap its paralyzing fingers around me.

The room grew still. Suddenly, the action is now, forever the present….

The Champion steps forward.

Everything is in slow motion. In my mind I am both fencer and observer. I see everything clearly, with an unhurried sense of peace and certainty. I hold my breath. Sound fades away.

The Champion raises his sword arm first, his foil point dancing in the light. His feet float above the floorboards, carrying him, like a huge wave, toward me. There is murder in his movement.

I feel the thump of my heart, the push of blood through my veins. Or is that the beat of the universe?

He comes on, but I hold my ground. I do not retreat this time. I won’t retreat, I tell myself, I won’t. Instead, I simply extend my arm straight into the Champion’s advance—a counterattack-- a stop thrust, a tactic as old as fencing. My foil is an extension of my body, of my nervous system. It is part of me, responsive.

The Champion has been ambushed. He did expect me to back down. He tries to change his plan. As he comes forward, he swings his blade in a huge circular parry, to scoop my blade helplessly out of the way.

With a tiny twist of my fingers, barely visible—the French call it doighte-- I deceive the savage, desperate sweep of his blade. Motion blends into motion with the softness of water meeting water.

The Champion, to his surprise, misses my blade entirely. It is there, but not there. Two bodies opposed yet working in perfect harmony.

Carried forward by his own momentum, the champion falls onto my waiting foil point. It hits him neatly square in the middle of the chest. The blade bows deeply, then relaxes.

I don’t hear the buzzer on the scoring machine, but I look over slowly to see one light, my green light, flashing.

Suddenly, I hear a voice. The director. “Touch left. Bout!” he announces in long drawn-out words, lingering forever in my ears.

The image of one touch freezes in time….

It was over. I looked at the Champion. The Champion looked at me. I had won. I had beaten him. We shook hands. “Thank you,” I said, and meant it. “Nicky, my boy…!” the Champion returned, crushing my hand in his giant paw. He meant that.

Still, at that moment, I felt like he was my best friend in the world. Maybe, in a way, he was. He’d inspired me to fence the best fencing of my life. He was, of course, a much better fencer than I was. I know that. And he would most likely always be that. But, in those brief moments of exchange and opposition, he helped me see how good I could really be. I’m sure he’d have chosen otherwise. Oh, well…!

A life was changed.

I glanced over to where Mr. Faulkner was standing.

He nodded once, then turned away, heading off to his office.

Fencers quietly began packing their equipment bags to depart, no one saying anything to me.

The class, for the night, was over.

When everyone was gone, I put the folding chairs away and slowly swept the fencing room floor.

Although this bout, this contest, this duel, took place over forty years ago, I remember it as though it happened only yesterday.

(c) Originally published in The Inner Game of Fencing, by Nick Evangelista (2000)