Once upon a time, when I was taking an upper level medieval history class in college, a student sitting right next to me made a disparaging remark about the eminent cleric and medieval historian Bede, lauded as one of the greatest intellects of 6th century Europe. The student categorized him as a “superstitious primitive” because he believed in miracles. The history professor, himself a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship grant recipient and respected expert on Medieval France, stared at the student for one long moment, and then said slowly, “And by what authority do you make this pronouncement?” The student was stopped in his tracks. “I just feel ….” The teacher interrupted him. “ “What you feel means nothing to history. By what authority do you disparage Bede?” The student had no answer.

So, what exactly did the professor mean by “By what authority …”? In point of fact, he was pointing out in no uncertain terms that the student’s opinion had absolutely no weight behind it, because the student had nothing to support his position. Neither facts, nor education, nor expertise, nor research, nor recognition as a scholar were in his corner. He was a student. Not that students aren’t allowed to make valid observations, but they should always be made from the standpoint of being a student, as opposed to an assertion made by a fully qualified individual. There is no democracy of ideas in scholarship. Nor should there be.

The student was, in fact, a loud-mouthed jerk, and so the professor’s remark actually did little to slow him down through the rest of the semester. As it often happens with jerks, this student was so full of his own self-importance, he had little room for facts, or a recognition of true knowledge or achievement. He was, as the 17th century fencing master Sir William Hope would have said, an ignorant.

This, of course, leads us straight into … fencing.

Hierarchy and Respect

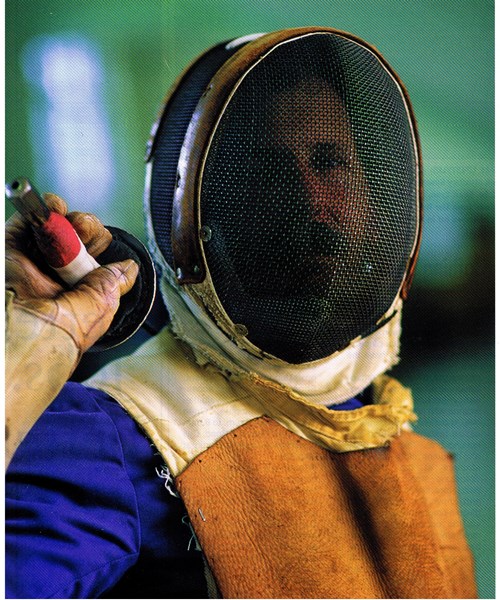

In fencing (at least the traditional fencing I grew up in over four decades ago), as in other disciplines, there is a hierarchy. There is the master and there is the student. To be a master sets one apart from the rest of the herd. There are also lesser teachers of fencing, but even these are still students aspiring to higher levels of learning which will render their instruction more complete. Modern fencing has designated other levels of “being in charge,” but these are not important to this discussion.

At one time, in fencing, the concept of “master” would have been understood by students and would have been respected without question. To dedicate one’s life to the learning of and teaching of fencing was the mark of a remarkable individual. A student, then, would never pit his understanding of fencing against the master’s. First, this would have been a blatant display of disrespect, and would have been condemned by the fencing community. Second, any self-respecting student would have been too embarrassed to even suggest he/she knew more than a master.

Today, unfortunately, where apparently the mere winning of a medal bestows “expertise,” hierarchy is given little regard. Perhaps, in a politically-correct world it is offensive to suggest that this person is in some way “better” than that person. Also, to accept mastery in another may place the mark of inferiority on one’s self. Besides, masters and hierarchies speak of other times and old-fashioned concepts, things out of step with modern life. Today, we have pundits, critics, commentators, reviewers, and those who tweet. Be that as it may, fencing needs mastery and it needs respect. It needs these things as binding forces to counter the effects of “anything goes,” because, when fencing can be anything anyone wants it to be—and it often is--it instantly becomes nothing. It is close to that now.

A question: Is respect in fencing even taught or required anymore? Many fencers no longer salute, or shake hands after a bout. Fencers are blatantly hostile to or scornful of directors and judges. Tantrums are common, as are childish victory displays. Is it any wonder that respect is in such short supply?

Fencing is a unique activity. But in many ways it simply mirrors the greater environment in which it resides. The foibles of our modern social structure infiltrate the fencing world. The mindless pursuit of success at any price, the fast-food mentality of instant fencing, the worship of the superficial, all traits of society at large, are to be found in present day fencing, and, for us, are magnified because we constantly hold these failings up to fencing’s traditional values -- which are based on the logic of the sharp point -- and find them wanting.

Those who accept these lesser values, of course, are in opposition to tradition. Tradition, to them, is old fashioned. Tradition is a roadblock to fencing’s “ever-changing evolutionary process.” Tradition, for them, is meaningless. They hold no respect for ideas gleaned from a time when sharp points provided fencing with its conventions, and they hold no respect for those who espouse traditional ideals. That one approach has a given meaning in context with the cause and effect of a sword fight, and the other is merely a manipulation of electronic devices doesn’t faze them. “That is what fencing is now!” is the usual reply. The understanding of the implication of one’s actions, one’s behavior, has no bearing on the matter. Fencing has somehow evolved from earlier times, the saying goes. But let’s get one thing straight, change does not necessarily denote progress. A cancer cell changes from a normal cell, but no one would suggest, once diagnosed with cancer, that they were evolving into a higher life form.

But one does not respect what one does not understand. In a world where everything is relative, and consensus of opinion makes things so, mastery means nothing to a fencing community where “I made the light go on the scoring box!” is looked on as the main criteria for excellent fencing. To one who cannot reason otherwise, a bent-arm attack is just as efficient and valid as one with a straight-arm. It has been argued in some fencing circles that the free arm in fencing has no bearing on balance. And yet, in circles where the free arm is not employed, knee and ankle injuries are endemic. Fencers are apparently just pulled to the ground randomly by gravity spikes. Or maybe they fall down because they are off balance.

Society, Equality, and Mastery

Society conditions us to think that everyone has a right to their say. “Freedom of speech” and “Constitutional rights” go together like bacon and eggs, night and day, Abbott and Costello. How can anyone criticize something that is a Natural Right, as defined by the eminent 17th century English empirical philosopher John Locke?1

I will do that now.

All men may be born equal under the eyes of God, but somewhere along the way, some achieve a higher level of mastery in certain areas of life than others. This achievement should be recognized by all for what it is. Mastery does not come without effort. There is a difficult rite of passage that must be trod. But respect isn’t always forthcoming. Many are unable to recognize true achievement; others don’t care to. Either way, there is no respect to be shown for simple mastery, especially if it opposes someone’s personal views about fencing. The rite of passage to attainment is not always understood. Someone’s “sacred” opinion, in the world of democracy, becomes just as valid, just as important, as the real knowledge gained through years of hard work. Opinion, generally emotional and without insight, should not be mistaken for knowledge; but it often is.

An opinion voiced with resolve is the battle cry “I’m just as good as you are!” If one examines the source of this utterance and finds it lacking, the obvious reply is, “No, sorry, you are not.” If an individual truly understands the reality of mastery, one also understands to gauge one’s remarks to his or her level of understanding. These would be called questions. In today’s world this gift of insight is a rare thing.

Internet Access and Opinion

The Internet is a great warehouse of and supporter of disrespect, when it comes to fencing, anyway. Well, actually when it comes to everything under the sun. At one time in the history of presenting one’s ideas, one had to have some level of expertise on a topic to have one’s ideas aired in public. One had to actually convince someone who was in a position of authority to take their ideas and display them before the world. This might have been an editor, a publisher, a board or committee, an investor, a patron, whatever. But the Internet has changed all that. The Internet is very democratic. It will accept, without question, anything. Now, anyone and everyone has access to an electric soapbox, via the Net, and opinions are aired openly and easily, without regard to their veracity. Anyone can forcefully voice an opinion, no matter how ill-informed or ignorant they might otherwise be. Find a online chat room, fencing or otherwise, and it will be rife with ignorance and disrespect.

Why so much vehemence? Here is one thing we know from the study of biological anthropology: when monkeys are afraid of something, they climb to the safety of the highest trees in the forest, and throw their own fecal matter down at the object they fear. Likewise, when people are confronted by a whatever that somehow threatens them, they retreat to the security of their computer, and let go with verbal equivalents of excremental monkey business.

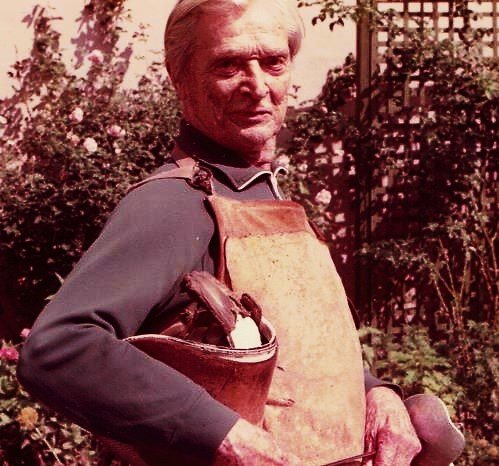

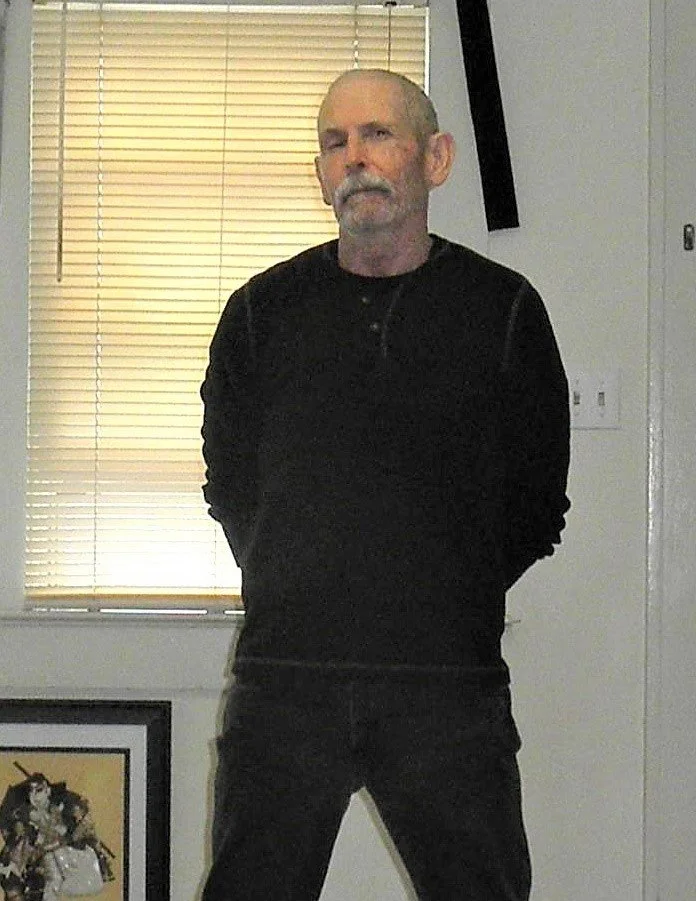

For my own part, I have been the subject of numerous Internet “discussions” over the years. Some of these, most of these, are not complimentary. I am used to this. When you are in the public eye, you have to develop a thick skin. I use myself as an example, then, not to complain, but to show the ease by which those who should not be making fencing-related observations, do. Those with time on their hands can be very “expert” from computer keyboards in the safety of their own homes.

One chat site I came across by accident actually devoted about 35 pages of conversation to the topic of “Nick Evangelista knows nothing about fencing.” There was no substance to the conversation. The attacks were purely ad hominem.2 One individual went so far as to state that he’d seen me in a tournament in Los Angeles in 1983, and that that I hadn’t even gotten out of the preliminary bouts. This was an interesting observation considering I’d retired from all competition in 1978. But one can say what one wants on the Internet, and who will contradict the remark? Every small fencing mind becomes an expert. Every unsupported observation becomes a gem of fencing wisdom. There is a strong lack of critical thinking to be found in these sage circles.

Book review sites are common places for individuals to air their ideas. The following are typical negative reviews, in this case from beginners:

For the record, I am an intermediate sports fencer with a great appreciation for classical fencing. My first coach used to annul points in class if she felt they weren't proper hits. Also, I fence foil and epee with a french [sic] grip. As much as I want to like this book, I find less and less reason to go back to it. A HUGE part of it is taken up by Evangelista's personal hatred of pistol grips ….3

We can stop here. Actually, if you combine all my references to pistol grips in The Art and Science of Fencing together, they would fill one page out of 288. 4

A review of The Inner Game of Fencing was based on “democratic spirit” and “consumerism” (but not fencing knowledge):

Ok, I am a new fencer, and a novice being critical of someone as famous as Nick Evangelista may seem a bit out of line at this stage of my career. However, I did buy the book and did read the book, and I suppose in this great American republic, that qualifies me to review his work. I found Mr. Evangelista's book to be a series of essays regarding his philosophy of fencing. The essays, are for the most part ungrouped by theme or topic, and tend to take on a tone that could only be described as a bitter rant. 5

People will see what they want to see, especially if they are ill-equipped to judge what they are reading. I might add, I did, in fact, group the essays by theme.

Finally:

I am an admittedly novice fencer, having taken up the sport only a year or so ago. I came across this book on Amazon and was amazed at the wildly divergent reviews of Mr. Evangelista's tome. The purist in me agreed with some of his views on classical fencing - his unapologetic bias towards the French grip versus the pistol grip, his dismissiveness {sic} regarding the use of speed and strength in favor of proper technique, and the recommendation that beginners learn foil before other styles of fencing. (I tend to be a purist on many sporting matters: baseball and football to be played on real grass, no designated hitter in baseball, playing basketball as a team, rather than individual sport, and using wound-core - instead of solid-core - golf balls.) Mr. Evangelista does tend to be bombastic - although he tells you that he is, up front. Simply put, he openly acknowledges his biases in favor of "classical fencing".6

Agreeing with me in “spirit,” the novice then goes on to wage a personal attack on me rather than addressing any real fencing issues. This type of stuff is typical of fencers schooled in the ignorance of modern fencing. Their refrains are based not on fencing but on feelings.

Another feature of the Internet attacker is his generally faceless quality. Many times, these individuals will hide behind a computer name or no name at all. At other times they may use their real names, but will tactfully leave their e-mail address off their reviews, so that they can’t be contacted. One ends up asking once again the main thrust of this editorial: “What expertise do these individuals possess that allows them to judge anyone? ”

Such judgments are offered unsolicited, and accepted and preserved by non-judgmental sources. Authoritative statements are never questioned, and the skills and experience (or lack thereof) of those who utter them never enter into the equation. Obviously, these folks don’t recognize their own lack of experience is an impediment to making valued verdicts. The Constitution of the United States gives them the right to speak, and so they do. Their lack of fencing etiquette, respect for authority and experience, allows them to express themselves in any way they wish. There was a time, of course, when no one would have listened to them.

A Study of Ignorance

So, why are criticism and hostility so easily forthcoming from individuals who should obviously be recognized by themselves as the least fit to offer expert comments? In a 2003 psychological study, titled “Why People Fail to Recognize Their Own Incompetence,”8 researchers David Dunning, Kerri Johnson, Joyce Ehringer, and Justin Kruger, found that many individuals regularly over-estimated their own abilities in matters of judgment simply because they lack basic the self-awareness to recognize their own personal deficiencies. The problem, then, becomes a self-perpetuating one of ignorance feeding on itself. The study concludes that if people are devoid of the skills they need to produce correct answers, they are also cursed with an inability to realize when their answers, or anyone else’s, are right or wrong. They therefore “cannot recognize their responses as mistaken, or other people’s responses as superior to their own.” If we apply these findings to the subject under discussion, we can see that incompetent fencers do not recognize that they are incompetent to make any kind of fencing judgments, and only do so because they don’t know any better.

Conflict

There may be other motivating factors involved in this matter. One theory prominent in psychology, called cognitive dissonance,9 suggests that confronting a specific reality that conflicts with one’s own experience may be extremely threatening to many people. It creates an emotional response that demands action. An individual will often resolve the emotional distress they are feeling simply by rejecting the messenger out of hand, rather than dealing with the issue of whether the messenger is correct or not. This resolves the problem without any possible threat to the individual. It also explains how hostility manages finds its way into fencing exchanges that should be based on logic and reason.

Conclusion

It is too bad when fencers are unable to recognize that they are students and masters are masters. The fencer may not realize that no matter how many medals they might have won that they are still not fit to impart fencing knowledge. It is also true today that fewer champions than ever before are becoming masters of the art. Why is this? The most obvious conclusion is that they are not competent to teach. The teaching of fencing and competing in tournaments are two different animals. Simply because you can make a light flash on a scoring box does not qualify you to expound on the intricacies of fencing. Until the fencing community at large recognizes this, we will continue to see the spirit of fencing diminished by the ignorant. This is not a good thing, even if they don’t know any better.

End Notes

1 John Locke (1632-1704). Sometimes referred to as “the Father of the American Revolution” because of his views on human rights.

2 ad hominum: attack the man, not his ideas.

3 Amazon.com, The Art and Science of Fencing, by Nick Evangelista.

4 I checked.

5 Amazon.com, The Inner Game of Fencing, by Nick Evangelista.

6 Amazon.com, The Art and Science of Fencing, by Nick Evangelista.

7 I never tell anyone I am being bombastic in The Art and Science of Fencing. The word “bombastic” means, “Characterized by important sounding but meaningless language”. Why would I say that?

8 Dunning, D., et al, (2003). Why People Fail to Recognize Their Own Incompetence, Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12,(3), pp 83-87.

9 The theory of cognitive dissonance suggests that people seek to relieve the discomfort associated with the awareness of inconsistency between two or more of one’s cognitions (beliefs or bits of knowledge). Gray, P. (1999). Psychology (3rd Edition), Worth Publishers.