Form and the Free Arm in Fencing: Then and Now

Nick Evangelista

Form and the Free Arm in Fencing: Then and Now

By Nick Evangelista

Angelo’s L’Ecole des Armes, 1763.

Much of the modern fencing world rejects traditional form as being old-fashioned and lacking any significant relationship to the modern sport. And, yet, as Maestro William Gaugler, founder of the first fencing master program in the United States, at San Jose State University, in 1982, points out so aptly in an article appearing in Fencers Quarterly Magazine (Fall, 2002), function—or the skillful application of foil, epee, or sabre—flows out of proper form. Established form, honed over centuries, can be accurately viewed as a “fine tuning mechanism” for fencing.

The great Helene Mayer (left), sometimes described by her opponents as a “brick wall,” because of her solid, unbreakable stance. A bout during the 1936 Olympics.

One might argue what constitutes “proper” form, but it is clear that the best form would be those attributes that produce a balanced condition for a fencer, so that he or she often achieves an expected positive result. On the other hand, no matter the success of any attack, collisions, falling down, repeated poking and jabbing, or bizarre twisting and gyrations would put said action outside the realm of good form. Well, it worked, anything for a touch, and the end justifies the means, should not be excuses for sloppy or brutal fencing. It should be noted that sometimes bad actions work simply because a fencer’s opponent made a bigger mistake than he or she did. To my way of thinking, the bottom line should be, What if these weapons were sharp? That should be a fencer’s line in the sand. That is what makes fencing fencing. Anyway, a sensible person might think that. Denizens of sport fencing world have disparaged me in print for saying this.

Practical Form Historically Speaking

Since traditional form in fencing was developed in an age when men were still fighting to the death with sharp swords, we might draw from this that the ideal form would, by necessity, be those actions which insured a good chance of survival in any personal combat situation. Being able to hit an opponent, say, without being hit would be a critical, since a tie with deadly weapons would be a disaster for all concerned. There then would be nothing fanciful, extraneous, or meaningless in one’s form, for these attributes would get someone killed very quickly. All rational fencers would shrink rapidly from behaviors leading to negative conclusions. Also, it would have been poor business practices for fencing masters to teach anything but good form—since anything else would produce dead non-paying students. It is from these realities that fencing’s practical cause-and-effect approach arose.

Traditional Versus Sport Approaches to Form

Formless sport fencing in action.

To achieve mastery, you need some something to anchor you, to give you a center from which to move freely and effectively. This is form. Or, more to the point, traditional form. In fencing, it is a way to direct the body as a balanced whole. But, today, there are those who have arbitrarily deemed traditional form to be obsolete. They reason that we aren’t fighting duels anymore, so they look to the scoring box alone to give what they consider “meaning” to their game. Furthermore, if making the light go on the machine is the point of it all, then cut out everything else that slows down this outcome, and focus just on the touch. Speed, strength, and aggression replace mastery. Why do they think this way? First, seeing fencing as nothing more than a sport--and the purpose of most sports being to accumulate more touch downs, goals, points, runs, or whatever than the other guy in a specific time period--they reduce fencing to its lowest common denominator. This doubtlessly comes from the single-minded sport mindset that asserts that winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing, a concept that has probably turned more athletes into assholes than any other sports concept. It also muddies the waters for fencing, because it refuses to admit that any sport could offer something beyond ego gratification or entertainment. The value of traditional fencing—and within traditional fencing, the purpose of form--never enters the picture. Form, to the modern sport mind is simply something some other people once did. But fencing isn’t just about feeding electric impulses to a glorified doorbell or amusing spectators. It’s about a process mastered, both physically and mentally, that changes the person participating in the mastery in a positive way. The acquisition of skill embodied in traditional fencing form becomes the touch, with or without technology. A great touch, denied by no obstacle, is just that, a great touch. Achieving this, the glaring lights and the strident buzzing of an intrusive mechanical appliance become redundant. If not that, we are left with… what? Random exchanges resembling freeway collisions, off-balance and cramped twisting and jabbing, the absence of clear, clean outcomes on the fencing strip, personal histrionic displays implying success to impress judges, and an increase in fencing injuries, both self-inflicted and those dealt to others.

Explaining the Free Arm

On guard and ready for action.

So, what is it specifically that has thrown modern fencing into a tail spin? Do modern fencers fence on their toes like ballerinas? Do they fencing with their eyes closed? Do they fence backwards with their blades stuck between their legs? Well, maybe some do, but that’s not the real problem. The problem has to do with the free arm. The free arm is the lynch-pin of traditional fencing form. Once a valuable fencing tool, the free arm’s only point today is to hang limply at the fencer’s side. Previously, fencers held up the back arm, straight out from the shoulder at a 45-degree angle, and then straight up at the elbow. The hand was relaxed.

So-called “advanced” sport fencers believe that holding the free arm up to be an affectation of another age, a useless holdover of polite, artsy, eighteenth-nineteenth century fencing, sort of a dance of the sugar plum swordsmen. Moreover, it is asserted by many sport teachers that holding the free arm up causes the shoulders to become tense. The rationale, then, is that dropping the arm “keeps the shoulders relaxed, and so promotes freer movement.” Sounds good. Unfortunately, it doesn’t work that way. Not even close.

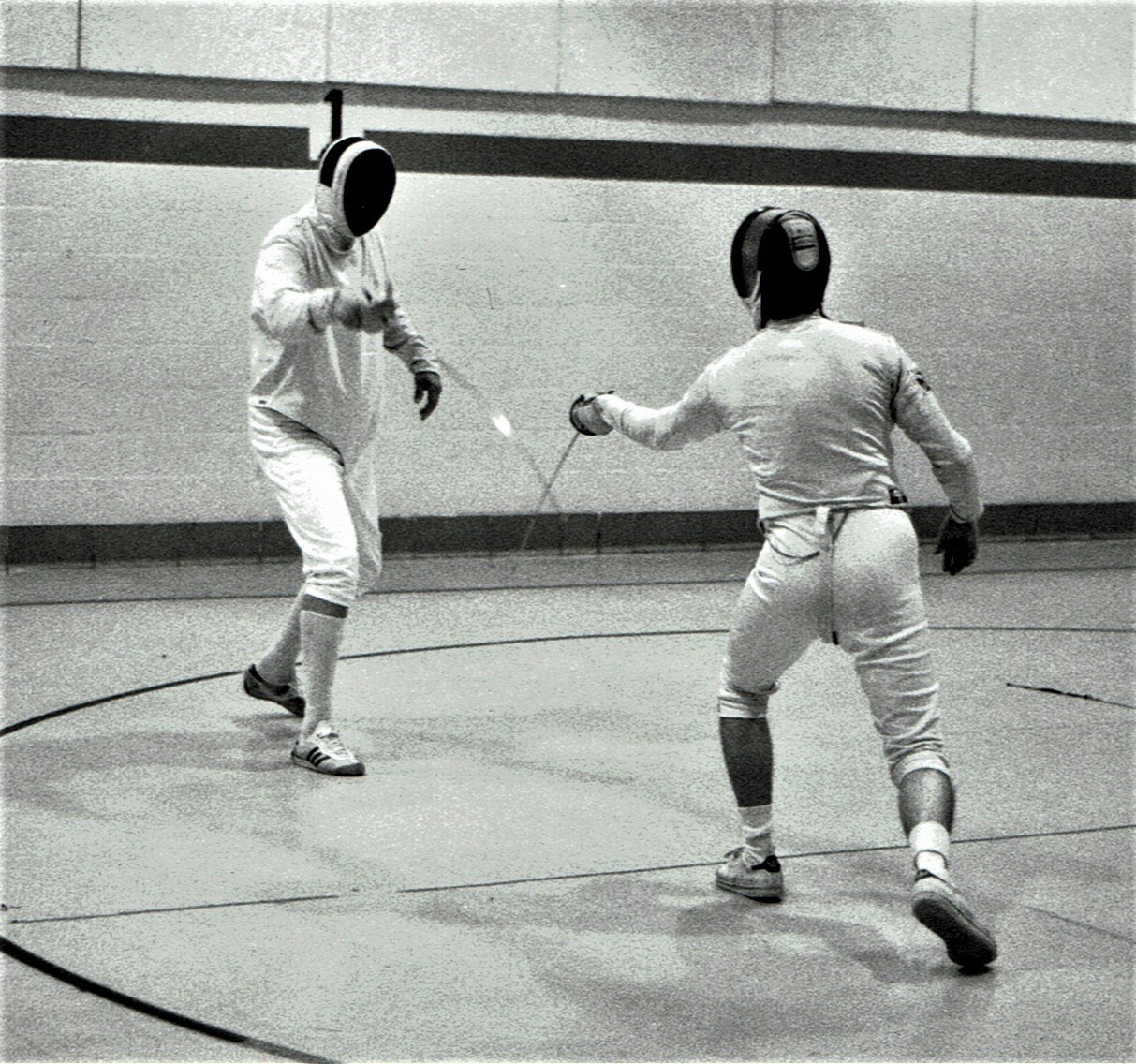

A highly credible centered lunge employing traditional form during a fencing bout.

The free arm does have a purpose in fencing.* Actually, it has a number of purposes, all of which are lost when the arm is allowed to dangle like a piece of overcooked linguini. Certainly, for students new to fencing, there is some initial tension in the shoulders when adopting the traditional fencing on guard position, but this quickly passes as you grow into it.** I have been fencing for over fifty years, and I can assure you that this is so. That being said, I would suggest that dropping the free arm is just a quick fix for lazy fencers.

So, what do we gain by employing the free arm in the traditional fencing style? First off, the free arm held up acts as a counter-balance, pure and simple. It keeps the fencer upright, promoting a balanced position whereby body weight remains distributed equally on both legs. This is a good thing for fencers who don’t want to fall down. Moreover, this balanced stance ensures the fencer will lunge from the back leg rather than stepping with the front foot, which, in turn, increases forward acceleration and distance covered. Holding the arm up at a forty-five-degree angle from the torso also keeps the body angled in relationship to an opponent, giving the opposition as little straight-on target surface as possible to attack. Finally, the back arm snapping back straight, palm up, serves as a rudder, like on a boat, enhancing point control. At the same time, the arm being thrown back will add to the acceleration of the lunge. As far as I can tell, all of these outcomes are positive things.

Salle de Kamikaze

Attacker and defender, both are leaning unsteadily through this awkward exchange.

Now, let’s look at the fencer who has been seduced by the Dark Side of the Fencing Strip. He drops his sword arm because this is what he has been taught to do. Opps! When he moves quickly, he loses his balance. Without a counter-balance, his weight shifts to his front leg. Now, all he can do is step or run or jump at his opponent. He is constantly off-kilter. If he has fenced for a while, he probably has, or will, hurt a knee or ankle--front, back, or both—since his weight shifts unevenly as he moves. Not surprisingly, sports medicine studies focusing on fencing injuries since the 1980s have cited the aforementioned body parts as the most likely areas to be injured in the modern sport, blaming “poor fencing technique” as the chief culprit for said mishaps. Serious head injuries caused by fencers colliding is also mentioned in the above surveys.

Their free arms dangling limply, neither fencer is in a position to establish a strong advantage over the other.

However, even without injuries, the fencer who adopts the above modern approach puts himself or herself into a less than advantageous position on the fencing strip. When the free arm is down, the sword arm shifts sideways toward the outside line, opening up the inside line; and the chest squares to the opponent, exposing the entire target area to an easy attack. The fencer’s feet immediately slip out of alignment, destroying any remaining ability to lunge effectively. Not surprisingly, the on-guard position being a holistic enterprise, when the sword arm moves to the outside, wider parries are the result. And, to be sure, dangling at his side, his free arm will not help him with his lunge, his balance, or his recovery. Many modern fencers, faced with the inability to perform an adequate lunge, simply resort to running, leaping forward, or jumping high into the air for their sole sources of locomotion. Is it any wonder that sport fencing matches so often descend into incomprehensible jab fests? This a dead-end for intelligent fencing.

But, to be fair, such fencers will always have relaxed shoulders.

Nice trade-off!

*As a reminder, when I am talking about fencing--unless I specify otherwise--I am talking about the dynamic traditional art and science of fencing that I was taught by my fencing master Ralph Faulkner, which is also the fencing I teach. When I talk about sport fencing, modern fencing, post-modern fencing, Olympic fencing, classical fencing, or historical fencing I feel like I am talking about the multi-dimensional Marvel Cinematic Universe.

**There is a dynamic in sport called the SAID Principle. This stands for: Specific Adaptations to Imposed Demands. This means that when we make new physical demands on our body, it immediately begins to adjust to these new requirements.