WHY?

Nick Evangelista

Why?

By Nick Evangelista

Why do I teach what I teach?

Today’s fencing, sport fencing, Olympic fencing, with its athletic explosions of frenetic irrationality, is as far away from true fencing’s intent, content, and spirit as fencing has ever been its centuries old existence. True, this current incarnation of fencing, the escrime d’jour, is the recognized purveyor of the game, but it is neither an art nor a science. It is simply organized chaos that seems to be growing more chaotic and incomprehensible as time goes on. God save us from the inspiration of the individual fencer. It takes but gives nothing back. There is nothing to give back. I could never support this, much less teach it. I need more, because from the beginning of my training I realized I was being shown a treasure. I had to pay for it with my time and effort and dedication; but, eventually, if I wanted it enough, it would be mine. It wasn’t the stuff of daydreams. It was a real system guided by both mastery of form and logic. Who could ask for anything more?

If you are a sport fencer reading what I have just written, you may well call my observations a rant, and proclaim to the heavens that I am full of it, and that today’s fencers are the greatest fencers who have ever lived. It wouldn’t be the first time I have encountered such sentiments from the sport community. My books on fencing, and my time publishing Fencers Quarterly Magazine have brought me numerous examples of sport fencing’s umbrage over the years.

As a final qualifying note, I do have a degree in History, which I would suggest, at least theoretically-speaking, steers me in the direction of critical thinking, a necessary ingredient in any kind of meaningful discourse. By way of this notion, in college, I had a professor who would tell students before essay tests, “I don’t care what your feelings are. Give me ten reasons for what you’ve stated is so.” I have always tried to follow this directive.

So, what about those greatest fencers who have ever lived? I have seen discussions online regarding these fencing people, and, by and large, the named all seem to be denizens of the twenty-first century. Not surprisingly, I suppose. By my estimation, these picks, based on the present state of fencing skill, simply show profound ignorance, bias, and a provincial sense of history. A short list of true champions might include such names as Lucien Gaudin, Helene Mayer, Aldo and Nedo Nadi, Ellen Preis, George Piller, Edoardo Mangiarotti, Alex Orban, Ilona Elek, and Christian d’Oriola. That they lived and breathed and fenced in the primitive twentieth century in no way diminishes their relevance to the fencing world when we talk of champions, real champions. Some of them actually fenced their entire lives without the dubious support of fencing technology. Once upon a time, fencers achieved greatness through measured ability rather than artificial manipulations designed to make sense of nonsense.

Aside from the aforementioned comparisons of skill, growing up in a fencing world where fencing was still fencing, I have personally witnessed the sport of fencing devolve to its present level for a half century, giving me a unique eye-witness point of view. This is why I have suggested previously that today’s champions would be nothing without their electronic crutches. By the way, I do not speak of electric fencing as a bystander. I have fenced and competed with electric foil and epee, and so I know their pitfalls. On the other hand, the best bout I ever fought in my life was fenced with an electric foil, so I also know, when used in moderation, their strengths. If anyone asks, I simply supply the necessary cautionary tales.

And what is the biggest problem I see with electrical fencing? What I worry about most is when I see skill and intelligence being measured in electronic interventions, because these “accomplishments” can be easily mistaken as valid benchmarks of human achievement. And this, in fact, is exactly what has taken place. Fencing as fencing has been dehumanized and robbed of thought in a mindless dash for an electrically generated impulse.

The fencing of post-modern concepts, the fencing of now, is a system victimized by a technological brainwashing of its own making. Behavioral Psychology, the science of response conditioning—that is, behavior modification--observes how bells and whistles, rewards and punishments, interventions, and modeling can alter thought and action. It really doesn’t take much effort, especially when the motivator possesses powerful incentives. Unfortunately, becoming trapped in something bigger than one’s self without a roadmap is a pitfall of modern life. Worse, as the system becomes more intricate and invasive, we become smaller and more dependent upon it. Instead of internalizing the system, the system internalizes us. When I watch videos of gymnasiums full of fencers running back and forth on fencing strips amid flashing lights and strident buzzers, all I see is assembly lines full of bean counters.

An illustrative true story: A few years ago, a student of mine was fencing for a large south-western university club, when, one day, he showed up for practice in his fencing jacket and jeans. An assistant coach looked at his pants, and asked, “Where are your fencing pants?” My student said, “Where I learned to fence, we always fence in jeans when we practice.” The coach looked puzzled. “You can do that?” He nodded, adding, with a grin, “And sometimes we even fence outside.” “You can do that?” the coach said again. “Oh, you must have had a very long extension cord.” Figure out the final reply for yourself.

Taking the above thesis beyond the fencing piste, I sometimes wonder if mankind isn’t already morphing away from Homo sapiens into some sort of hybrid, perhaps Homo electronicus, a human that can neither think nor act effectively without the benefit of artificial prompts. Can anyone these days, married to their cell phone, operate effectively in the world without their electronic teat? Are we that far away from Homo electronicus right now? I do not own a cell phone/smart phone/iphone. I have never recognized a need for one.

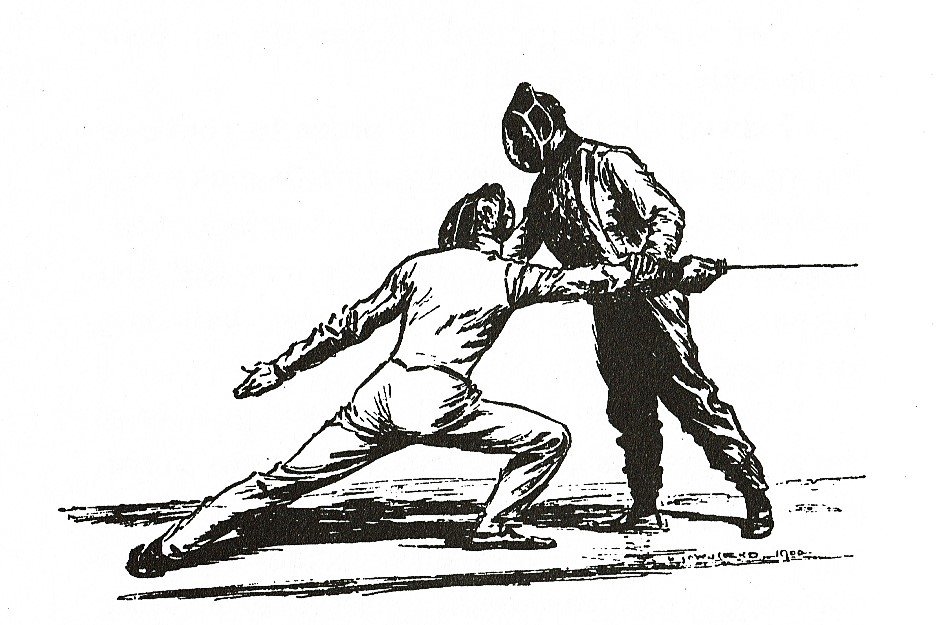

For my own part in the story of our species, I teach fencing as I always have, as a human skill supported by the mastery of a long-perfected system. When I wrote my book, The Art and Science of Fencing, in 1996, I said, without hesitation: “It is human beings who carry out the manipulation of the foils, epees, and sabres. We aren’t machines on the fencing strip. Fencing isn’t some cold, impersonal mechanism, but a vigorous, red-blooded, highly personal expression of mind and body.…Human experience, after all, is the essence of our art.…It is important for beginning fencers to realize they are part of something deeply rooted in man’s existence.” Today, twenty-six years after setting down those words, I still believe this more than ever. I will always champion human mastery over technological interference in fencing.

This is why I teach what I teach.